Climate Change Part II: Why Don’t We Care?

Now that we’ve talked about the ins and outs of climate change, its devastating effects, and how we can slow them down , it’s time to delve a little deeper into the topic. One article simply isn’t enough. Did Sir David Attenborough stop making documentaries about our strange and beautiful planet after the first one in 1954? Of course not! He kept making one after another, hoping that one day his viewers would actually do something to protect it, rather than just breathlessly staring at beautifully captured exotic locations while being enchanted by his angelic voice explaining the mating behaviour of rare penguins.

Why, with all this terrible information available about climate change and its devastating effects, do we still not care enough to make a difference? Why have all geopolitical efforts so far failed miserably? And is there a solution to the problem that won't end in the complete destruction of humanity? Find out in Climate Change Pt. II: Why Don't We Care?

History

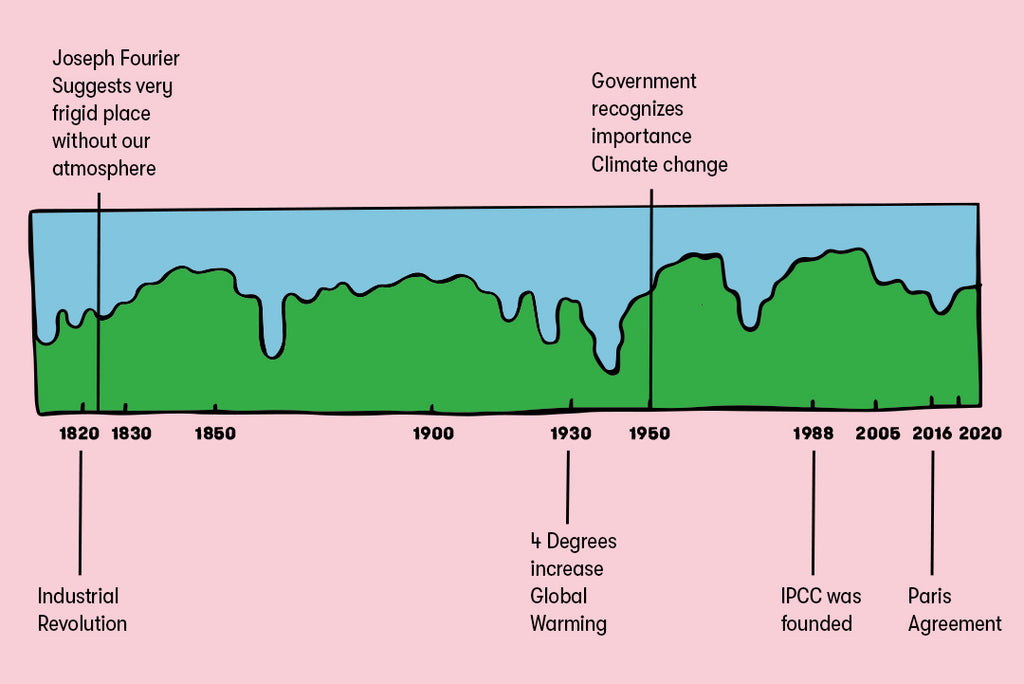

Ignoring the signs of global warming is nothing new under the sun – mankind has a bit of a skepticism when it comes to climate change. Concern about carbon dioxide in our planet’s atmosphere dates back to 1820, when the transition to new manufacturing techniques and the rapid exploitation of natural resources during the First Industrial Revolution forever changed the way we humans relate to our environment. In 1824, French mathematician and physicist Joseph Fourier was the first known figure to suggest that, without our atmosphere, Earth would be a somewhat cold place (read: too cold to support life). Around this time, the “greenhouse effect” was also discovered. Just to refresh our memory: that’s the increase in atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O) and ozone (O3) that are the cause of global warming (2).

As early as 1930, it was known that doubling carbon dioxide emissions could lead to a 4-degree Celsius increase in global warming. The mid-20th century was the first time in history that government systems around the world recognized the importance of their involvement in climate change. However, it was not until 1988 that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was founded, now known as one of the most influential bodies (2). Since its foundation, the IPCC has been publishing annual reports on climate change, confirming that our planet is getting warmer and warmer.

2016 marks the year of the Paris Agreement. 184 countries committed to reducing carbon emissions produced by human activity (aka anthropogenic emissions). Although since then, a few things have happened. Like Trump pulling the United States out of the Agreement, for example, or the world realizing that most countries will not meet their climate goals by 2030. And that, essentially, if we fail to meet these goals, the financial losses will be astronomical (read: $2 billion per day) (3). Worse still: the damage to the environment will be irreversible. In 2020, atmospheric CO2 reached almost 420 parts per million (PPM) for the first time in history, and CO2 emissions from burning fossil fuels have been recorded at 35 billion tons (4). Carbon dioxide contributes the highest percentage of global greenhouse gas emissions, followed by methane and nitrous oxide (5).

Because we don't care

When it comes to pro-environmental behavior, one thing is certain: we humans like to ignore complex, intangible problems. We have a tendency to ignore or invalidate problems that we don’t directly experience ourselves. Like climate change. The root of this problem goes back to when we were hunters and gatherers. People’s minds evolved in a world where there was a tangible, visceral connection between action and consequence. For example, if a tribe cut down all the trees in their area, they would run out of wood. If they hunted all the animals in their area, they would run out of sources of meat, fur, etc. The consequences of their actions were immediate. One big difference between modern life and hunter-gatherer times is that people today rarely see, feel, touch, hear, or smell how their behaviors affect the environment. When we buy food, we don’t see how food is grown, harvested, processed, or transported—we don’t see how it is grown, harvested, processed, or transported. If a product is out of stock, it is normal to assume that the supermarket will have restocked the shelves the next day (6).

And then there are the glaciers. It almost goes without saying that fresh water is essential for human survival, and it just so happens that about 90 percent of the world's freshwater resources are found in Antarctica, in glaciers. Yet because we don't see the melting of glaciers or their effects on our daily lives, scientists are having a hard time convincing the world that this is a fundamental problem that concerns us all.

Is there still hope?

It was Aristotle who said, “what is common to many is least cared for.” We are part of a system that motivates us to increase our own profit without limit, in a world that is limited. No individual wants to sacrifice and reduce the size of his utility, because it represents only a small fraction of a problem. The same is true for businesses and even governments.

But many researchers and economists believe that the global COVID-19 pandemic is the perfect time for the business world to re-evaluate and restructure its policies along more sustainable lines. These times call for strong government action, and the call for innovation seems stronger than ever.

For many years we have measured a country's 'success' by looking at GDP (Gross Domestic Product), but many economists argue that GDP is too narrow a measure and should be replaced because it does not take into account the environmental impact, the impact of economic growth (which, as we discussed earlier, can add up to billions of dollars per day over the long term). If, for example, there were a major environmental disaster, a lot of money will be spent on recovering from it, which will, ironically, cause GDP to grow. So yes, GDP should probably not be the primary goal of economic and public policies that governments should focus on… (11).

Many economists argue that more innovative business metrics and models could and should be used instead of good GDP. One example of this is the Doughnut model. In this model, an economy is considered prosperous when all twelve social fundamentals are met without exceeding any of the nine ecological ceilings.

The concept of these ceilings, or planetary boundaries, was developed by Swedish professor Johan Rockström in order to quantify “the safe limits outside of which the Earth system cannot continue to function in a Holocene-like stable state.” (12) Overshoot threatens the ability of systems to take a hit without collapsing. In fact, we wrote an article on Earth overshoot , which we also recommend reading.

What can we do?

Changing the course of history is rarely a one-person job, and it will take some serious government action to really turn things around. Still, we as individuals can do our part by raising awareness and setting the right example. Since livestock products are among the most resource-intensive to produce, eating meat-free meals can make a big difference to greenhouse gas emissions. So check out our nutritionally complete meals that not only have a 12-month shelf life, but are also vegan.

However, the easiest and perhaps most important way to make an impact is to voice your concerns. Talk to your friends, family, colleagues or even local government officials. Let your concerns be heard and encourage others to take the issue seriously! Together we can make a difference.

Sources

- IPCC. 2014. Climate change 2014: synthesis report – summary for policy makers. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- Le Treut, H., R. Somerville, U. Cubasch, Y. Ding, C. Mauritzen, A. Mokssit, T. Peterson and M. Prather, 2007: Historical Overview of Climate Change. In: Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- Roberts, D. (2019, November 5). Vox . Retrieved from The Paris climate agreement is at risk of falling apart in the 2020s.

- Global Carbon Budget - Friedlingstein et al. (2019),Earth System Science Data, 11, 1783-1838, 2019, DOI: 10.5194/essd-11-1783-2019.

- IPCC 2018. Climate change 2018: special report – Global warming of 1.5°C. Summary for policymakers. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- Griskevicius, V., Cantú, SM, & van Vugt, M. 2012. The evolutionary bases for sustainable behavior: implications for marketing, policy and social entrepreneurship. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing , 31(1): 115-128.

- Pauleit, S., Zölch, T., Hansen, R., Randrup, T.B., & van den Bosch, C.K. (2017). Nature-based solutions and climate change–four shades of green. In Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change Adaptation in Urban Areas (pp. 29-49). Springer, Cham.

- Conway, E.M., & Oreskes, N. (2014). The Collapse of Western Civilization: A View from the Future. ColumbiaUniversity.

- Cohen, D. K. (2019, March 26). Sea levels are rising and we don't have a Plan B.

- Falham's Street Mental Model, The Tragedy of the Commons.

- S. Hill. 2020. A post-pandemic research agenda. LSE Impact Blog.

- Rockström, J., Steffen, W., Noone, K. et al. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 461, 472–475 (2009).

- Davis, E. (2018). WWF Report Reveals Staggering Extent of Human Impact on Planet .